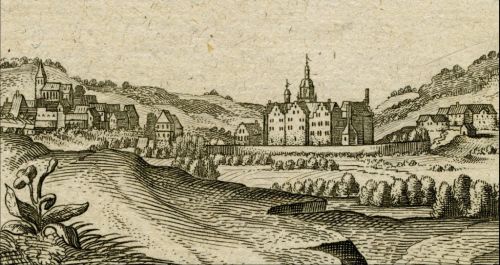

[Original Kupferstich von Merian von ca. 1650] |

The Merlau Schloss

An excerpt from the history of the Merlau Schloss. Some of it you may already know, some may be new to you. We hope at least that it will be interesting for you.

|

Where it began

Landgrave Philip the Magnanimous died on 31 March 1567. In his will he divided his inheritance among his four sons. Ludwig IV received from his father the land on the Lahn with Marburg, Grünberg, Romrod and Merlau. These inherited lands made it necessary to create new residences. His new buildings included the construction of Schloss Romrod in 1578, the Grünberg Schloss in 1578 and Merlau schloss in 1583 - 1592.

The Construction of the schloss

From 1583 to 1591, Merlau was a hive of activity. In its long history, the village had never seen so much activity and may never have seen it again. Hundreds of workers came and went, a source of great excitement for nine long years. Specialists came from far and wide. Stonemasons, carpenters, glaziers, tilers, roofers and blacksmiths. Toolmakers to keep the equipment sharp and in order. Office workers who kept records of purchases and wages. And labourers who fetched and carried everything. The workers were hungry and thirsty, which meant an army of carters bringing in food and drink. Accommodation would have been needed. And where? Presumably near the village?

Who was the builder?

Landgrave Ludwig IV commissioned his master builder Eberdt Baldwein to build Merlau schloss. He first visited the building site in August 1580. Baldwein often travelled back and forth between Marburg, Merlau and Romrod, accompanied by his craftsmen, to discuss his plans with them at the building site.

Who was responsible for the work?

The Marburg authorities appointed Albrecht Weber to manage the work. Albrecht's job description included;

"He is to be our scribe there, have his residence in our house in Merlau and see to it that no wrong is done there. He shall always faithfully warn against harm, also not cause any himself, and behave responsibly towards our rentmaster in Burg-Gemünden and our master builder in the execution of our construction work."

He was responsible for ensuring that the workers did their work and that they were paid accurately according to the hours worked, by "keeping a record of every day and every hour and not paying or accounting for a whole, half or quarter of an hour more to any man than he works".

As if that were not enough to keep him busy, he also had to check all deliveries of building materials and "keep a proper inventory of all the tools we have in our name that are needed for our work.

Building, as well as of roofing and carpentry nails, other metal, window panes and anything else that is our responsibility, including what is added or removed at any time".

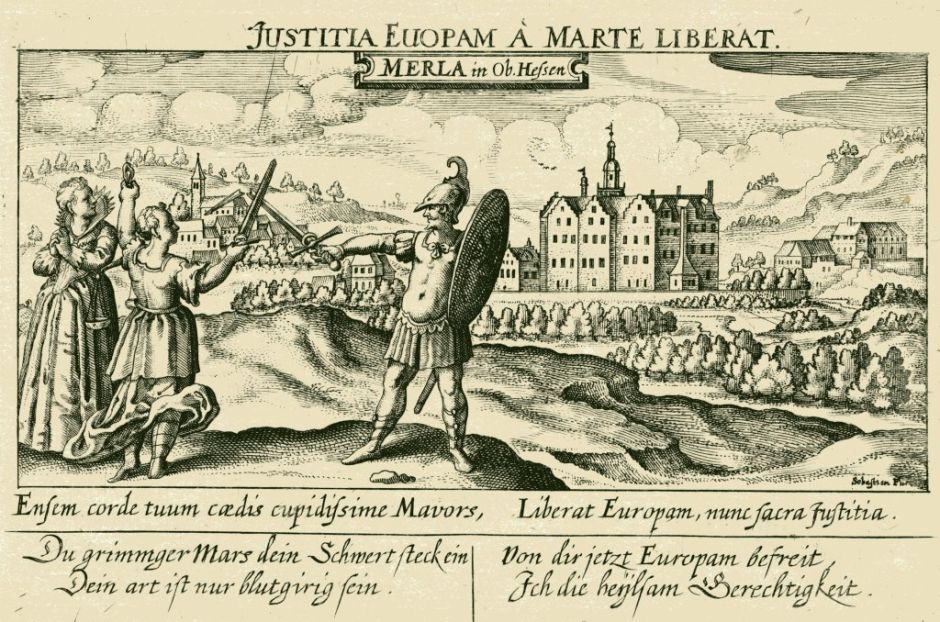

Kupferstich von Meisner von ca. 1630

The chronicler Wilhelm Dillich (called Scheffer) made an engraving of the Schloss after a pen and ink drawing already made in 1591. The view of Merlau, seen from the south, shows the Schloss in the centre, the village and the church on the left and the outworks on the right.

An entry in the Salbuch of the Grünberg district from 1591 briefly describes the Schloss. It says: "In the village of Merlau the landgrave has a beautiful princely Schloss, a house with gables, a lined moat all around, two drawbridges together with a church and a chancellery; also a pleasure garden and in the courtyard a fountain with a stone bowl, which is fed by a spring that rises in the field in front of the Burgwald, which is enclosed in a stone house. This spring also supplies the large kitchen"

The entire complex was built in the style current in the 16th century. The architecture was broadly in keeping with the German Renaissance style and apparently resembled the Schloss in Romrod and in Giessen.

Life in the Schloss

Landgrave Ludwig IV had retained his seat in his Marburg residence and placed the administration of Merlau schloss in the hands of his officials. After the death of Ludwig IV in 1604, however, his widow Maria lived in the Schloss. In 1611, the princely widow married Count Philipp von Mansfeld in her second marriage. This wedding celebration must have been a great time for Merlau.

Maria was still here in 1613, especially as the plague had broken out in Laubach and other places in the area. But as time went on, the Schloss was used less and less and Romrod schloss became more popular. The Schloss remained under the administration of the landgravial officials and gained a certain reputation, among other things, because of the fish farming in Merlau.

The Thirty Years War

During the Thirty Years' War, Merlau schloss served as a place of refuge for people from many surrounding villages. In May 1647, Merlau and the Schloss were captured by troops from Lower Hesse under General Mortaigne. The commander of the Schloss fled to Giessen with some of his soldiers. Those who remained in Merlau joined the Lower Hessian troops, which was probably a wise move under the circumstances. A year later, the Peace of Westphalia brought peace to Europe and, of course, to the inhabitants of Merlau. There are few records of how the inhabitants of Merlau suffered during this invasion, but there is no doubt that they must have suffered.

The pressure of war

For over a hundred years, no foreign soldiers were seen anywhere in Germany. But then came the so-called Seven Years' War in 1756.

In 1756/57, the Royal Prussian Jager Corps was quartered here. The officers were quartered in the Schloss and the soldiers in the village. During this time, the Saxon cavalry cleared the ripe cornfield to feed themselves and their horses, while the Hanoverian cavalry, who arrived later, cleared out the barns.

At the end of March 1759, the allies under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick set out to drive the French out of Hesse. The storming of the schloss in Ulrichstein took place at this time. There was fierce fighting in the surrounding villages and many of the defeated troops sought safety at the Merlauer Schloss.

But Merlau was hit hardest in 1762 by the French army, which set up camp on the ripening summer fields of Merlau. Here they found sufficient water in the local ponds and the Linnes forest supplied them with wood. As usual, the officers once again occupied the Schloss.

In November 1762, the Prussians and the French concluded an armistice at the Brückenmühle below Amöneburg and the fighting ceased. However, the Schloss and the village had suffered greatly during this time. The Schloss was very badly damaged and the people's stables were empty of cattle, pigs, sheep and chickens. In fact, everything that was useful for the armies was taken from them.

As so often happens after a war, a long period followed during which the various parties argued about what damage had been done, what furniture had been burnt or stolen and who should pay for the damage. No doubt the owners of the Schloss were paid more than the owners of the empty barns. That was always the case.

Then came the French Revolutionary Wars

About thirty years later, probably just as peace was returning to Merlau, the Prussians returned, followed by the Austrians, and marched through Merlau on their way to Marburg. The Schloss once again offered them a comfortable place to stay. There they found water for the horses and the villagers barns were once again emptied. The people of Merlau had to put the Schloss in order and arrange for the delivery of food and other supplies from Grünberg.

In the spring of 1797, a French lazerette or field hospital was set up in the Schloss, where it remained for 28 weeks. The doctors lived in the Schloss and incurred a wine debt of over 5000 guilders during their stay. The sick and infirm French were collected from a wide radius and everything the military hospital needed had to be brought to Merlau, and Merlau had to pay for it. The interior and exterior of the Schloss suffered considerable damage during these years and by the beginning of the 19th century the Schloss was nothing but a ruin.

The Schloss Chapel

The very last part of the Schloss that remained in use was the church. The Merlau village church was in such poor condition that it could no longer be used and instead services had been held in the Schloss chapel since at least 1777.

In 1813, the parishioners asked to be allowed to use stones from the Schloss ruins to build a new church in the village. This request was granted, partly in view of the unrest and destruction that Merlau and its inhabitants had suffered. However, this decision was also considered sensible because the material, if not donated, would probably have been stolen anyway. The master builder, Major Sonnemann, reported that he had noticed that the doors of the Schloss chapel were completely open because there were no locks left on the doors, and when he asked the Schultheiss for the reason, he was told that the locks had been stolen and that it would be pointless to have others fitted because they would also be stolen.

The last days of the Schloss

In the years that followed, there was much back and forth about the future of the Schloss, about the condition of the building and about individual items such as the great Schloss clock and a valuable bell that once hung there.

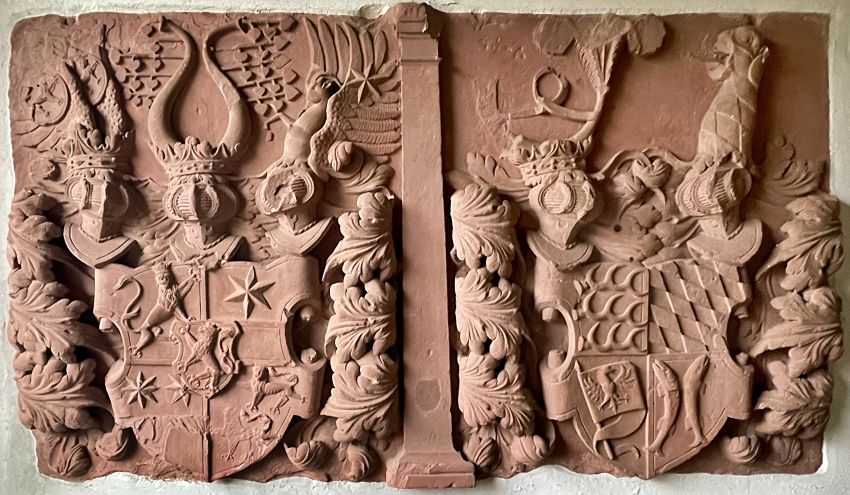

For some time,these letters were interminably exchanged without coming to any conclusionuntil finally, in 1823, the municipality of Merlau bought the Schloss ruins and used them as a stone quarry. There are many houses in Merlau that were built with the stones of the Schloss or partly with them. The Merlau church was finally built in 1853-1857, also with stones from the Schloss ruins. The double coat of arms of Landgrave Ludwig IV and his first wife Hedwig von Württemberg, the only remaining witness from times long past, can be found today in the church porch.

The coat of Arms that once stood above the entry to the Schloss